Sheila Gaffney

Reflections on the Good, the Bad and the Ugly

Reflections on the Good, the Bad and the Ugly (see Figures 1 and 2) is positioned through an account of an archive site at a particular moment in history - the Tate. Germaine Richier's L'Eau 1953-4 and Reg Butler's Working Model for ‘The Unknown Political Prisoner’ 1955-6, were both viewed by me at what is now known as Tate Britain in the late 1970s. Weaving textures of childhood influence, imagination and my own aspiration to sculpt in the finest tradition, this work extrapolates the detail of my sculptural thinking through making.

Fig 3: Sheila and Bernadette with the new record player, archive photograph, November 1968

The Frame of Working Classed Childhood

In 1966, a chart topping film theme playing across the airwaves concretised my belief that categories are a way to think. Ennio Morricone's musical composition for Sergio Leone's spaghetti western The Good, The Bad & The Ugly was launched as a single prior to the film's release. Although it had been edited to become a popular theme tune for commercial gain it still exhibited the compositional innovation for which he would become renowned. Within this composed score he introduced characterisations and identities....here it comes, the gunshot, the whistle, a squeaky water wheel, the tapping of a telegraph, the dripping of water, the buzzing of a fly, the sound of an approaching train. The quotidian sounds were operational in the overall musical composition. This music was diegetic, coming from a source known to exist in the world. It was part of what is known as ‘Musique Concrete’, which was the experimental technique of musical composition using recorded sounds as raw material. The score in its own right introduces musical signifiers such as military bugle calls to represent armies; a soprano voice that feminizes gold coins; the sound of a coyote to highlight the untamed personality of one of the protagonists (Leinberger 2004: 22). Within its own body of text, it sonically narrates the agents moving within the context of the fictionalised civil war.

In life writing and memoirs such affective examples of social context are not unusual. We understand and accept that diegetic objects have currency in life writing. Janet Street Porter charts the narrative of her young life through broadcast registers such as the ‘radio was on continuously throughout our meal of overcooked vegetables, meat and potatoes’ (Street-Porter 2004: 513). Grayson Perry opens his memoir with a description of Tom Jones booming out of the gramophone (Jones 2006: 159). Hilary Mantel uses the gramophone and radio to create metaphors for her own childish ability to invent visual narratives (Mantel 2003: 43). The affects of generic soundtracks are important not only in specifying moments in time, but framing them in geographically located social class positions (see Figure 3). However, in my case, this recollection also marks a somatic moment when I am aware that what I see, hear and feel, through bodily register, becomes part of my knowledge for life modelling (which I think parallels life writing). I find the autobiography in the questions I ask, so that I may offer answers with a wise accuracy. I have therefore included the diegetic, that is, elements that are perceived as existing within the world, depicted in the artworks as part of my making narrative.

By the time the film screened (and screened on broadcast platforms various through my lifetime) it was my benchmark experience for visual and aural embodiments exploiting characterisation and categorisation. This is a backdrop to my own cognitive development and an example of the ‘unthought known’ (Bollas 1987)1. My comprehension of this musical construction encouraged my own making of categories and rules for ‘good’ and ‘bad’ when encountering cultural phenomena. I now claim its effect in my own classificatory game, which has been invented to steer a path confidently through the 'civil war' known as British Sculpture's evolution in the twentieth century.

1 The ‘unthought known’ is an accepted psychoanalytical idea formed by Christopher Bollas which stands for those early schema for interpreting the object world that preconsciously determines our subsequent life expectations. In this sense, the unthought known refers to preverbal, unschematised early experiences that may determine one's behaviour unconsciously, barred to conscious thought.

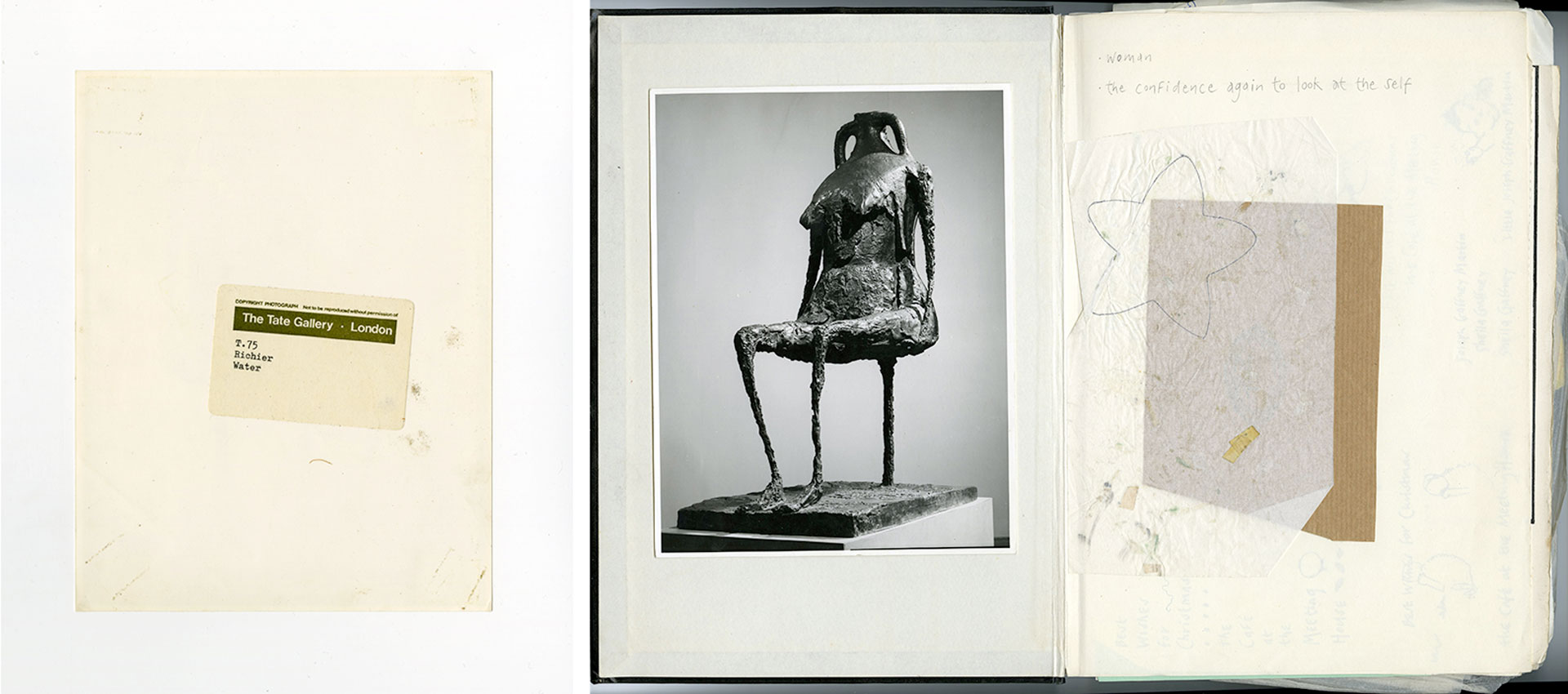

Fig 4: Germaine Richier, Water, 1953-4, Bronze Sculpture, 1331 x 640 x x983mm [T00075] © Tate, London 2015

Fig 5: Reg Butler, Working Model for 'The Unknown Political Prisoner, 1955-6, Steel and Bronze on Plaster Base, 2238 x 879 x 854mm [T02332] © Tate, London 2015

The Archive

I think the year is 1979. I am standing in the Tate as a student anxious to understand an agreed set of conditions firstly, to define sculpture, and secondly, to define a sculptural practice in which I could work. It is London’s only Tate Gallery, then in its pre-1988 layout, the pre-Nicholas Serota era when displays were static, demonstrating historic subject specific evolution through narrative exhibition. The original Tate at Bankside then exhibited a permanent history of European sculpture which mapped well against Albert E. Elsen’s Origins of Modern Sculpture:Pioneers and Premises (1974) which then continued to include contemporary British sculpture. An encounter with two pieces in this displayed story of sculpture become significant emblems in my own mental modelling in and through sculpture. This is the site of an encounter in an archive which triggers an antagonism between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ that has driven my sculptural practice from then to now.

I am a first year student in the sculpture department at Camberwell School of Art & Crafts, equipped only with inherited ways of understanding. Without rules for analysis I exercise my inbuilt belief in categories and characterisations bringing forward my know-how from lived experience where I become aware of meaning in what I see, hear and feel, through bodily register. I conducted a game of hide and seek in my head in order to track proximity to a credible definition when looking at sculpture, quantifying when I was ‘warm’ or ‘cold’ in my search. In my ‘Find Sculpture’ game of hide and seek, the category of 'hot' would include sculptures from the ancient world such as Cycladic figures, Venus of Willendorf, Assyrian reliefs, Egyptian carvings and this implied that I would be very close to finding my sought answers in an engagement with them. The McAlpine group1 which were the relatively contemporary and ultimate part of the Tate narrative were 'freezing' (diagrammatic, bombastic, dictatorial – no subjective or political trace) and the categorical assessment suggested nothing to be gained here.

Richier’s L’Eau (see Figure 4) and Butler’s Working Model for ‘The Unknown Political Prisoner’ (see Figure 5) were polar opposites in various ways (always useful in a puzzle and a game) and yet linked in the genealogy of British Sculpture. Although generated at the same historic moment, one was by a British man and one was by a French woman. Butler’s Working Model for ‘The Unknown Political Prisoner’is a profoundly powerful small work, where the sculpture is conceived in the spirit of public art and serves the voice of the nation. Butler was to have prominence in the British sculpture establishment and the UK art schools. He was one of the British sculptors who had been grouped within Herbert Read’s notion of the ‘Geometry of Fear’2 for their ambition to express states of mind related to post-war period fears and anxieties through figurative sculpture. The themes, tropes and material handling by this group won them a ‘warm’ category in my classificatory game.

The other work L’Eau (Water as the label told us) by Germaine Richier was the one work in this display that sat outside of the main gallery narrative. It is a larger than life black patinated bronze sculpture in the high tradition of life modelling. Its form evidences the studio procedures for sculptural life room practices and displays the necessities of armature building, open surfaces of unresolved handled clay and a highly resolved plastic surface contributing as parts to its overall confident compositional harmony. Through the form of the work I encounter woman-ness which is my own recognition of living in a female body. The highly resolved areas of tightly modelled clay around the sternum, shoulder and breast areas of the body effect an experience of embodied woman, which holds in material form what I know. There is no face or head in the literal sense. A diegetic clay amphora assimilates seamlessly into the bodily presence of the work. And it is not surreal, it is real.

It was key for me that L’Eau has been made by a woman. This was unique in the collection. The work had been made in an era when there was no feminist discourse available to comprehend or ‘hold’ Richier’s work (Wilson 2005). I am looking at it in a moment when Feminist discourses are however coming into play, but I recognise that it inhabits the male, masterly tradition traceable to August Rodin and Emile Bourdelle. L’Eau/Richier is at odds with the story, she is not in Elsen’s books, even when he includes Giacometti, Moore and Hepworth in his Modern European Sculpture 1918-1945: Unknown Beings and Other Realities (1979). L’Eau presents the female form in sculpture from a differently authored position than that of the male canon I am acquainted with. It clearly embodies the subjective within it – this gendered body is not the muse of the male sculptor. This difference is positioned at odds to the historic trajectory, however, it is included in Tate’s authorising narrative because history now acknowledges the influence of Richier’s work on our ‘Geometry of Fear’ of British sculptors of the post war period (Wilson 2005). And yet, there is no information I can find about this work to own and help my thinking through it. There is no postcard for sale or accessible monograph in the bookshop. At the time, I had to pay to order a photograph of L’Eau from the Tate archive as this was the only way I could source an aide-memoire of the work. A hand printed black and white ten-by-eight-inch print arrives by post some weeks after (see Figure 6). The photographic image of this significant form has now become a handmade object in its own right and I have always treated it like a trophy or saintly relic. It still sits sentinel amongst the saved texts from literary sources in my working sketchbooks today (see Figure 7).

Fig 6: Tate label on the back of Richier photograph purchased in 1979, archive document

Fig 7: Black and white Tate photograph (1979) saved in artist's 1989 sketchbook, archive photograph

In my encounter with Working Model for the ‘Unknown Political Prisoner’, I cannot block my consciousness of Butler’s later (then contemporary) works produced since this prize-winning maquette. They are a series of life-size and life-like painted bronze sculptures of naked girls and they present their images in my mind when I am thinking about his work. These recalled images are not welcome visitors as they are works which affront the thinking woman – I do not really want these images in my head. They were displayed in his 1983 solo exhibition at Tate, and it is worth noting that one of them, Girl on a Round Base (1968-72) is in the current Tate archive, outrageously purchased in 2001. These works shared characteristics in their manifestation: their bodies arched in an overtly erotic manner; they possessed ample white flesh bulges gathering in soft, round folds. Their heads would be flung back or pouting forward demonstrating some sort of distortion such as being upside down; their lips were generally parted with eyes open. Hairlines would be straight to emulate that of a doll (Tate online: 2015). They all had bald pudenda which were consistent in their prominence, annotated with paint to engender a life-like fleshy verisimilitude of what is commonly called a private part of the body. According to Butler, the absence of pubic hair came from his inability to make them sufficiently sculptural. These works were filmed and quite candidly broadcast by the BBC in 1974 when I was a teenager. This recording is still available now online in an existing BBC archive (BBC, 1974). In this film Butler is challenged about ‘their detailed genitalia’. He responds repeating the term ‘fanny’ twice (saying ‘they’re not throwing their fannies in your face’) and uses the term ‘tits’. He says ‘They're about in particular what I feel about women, they're about one's feeling of lust, one's feeling of compassion... they're sculptures about women.’ (BBC, 1974).

His 1950s sculpture, for the monument to The Unknown Political Prisoner, on the other hand, is a lean, economic meaningful lesson in making sculpture only be as big as it needs to be. I have to admit this is powerful. I want to learn from it. But it is impossible to view this politically intended sculpture for which I can find some formal admiration without the backdrop of an oeuvre that hurts me. Encountering the ‘Girls’ are not internal images that leave you. They pornographically enter your psyche and stay on your internal hard drive. I am angry that I carry their imprint inside me. My very being with all the potential I am entitled to fuflill in my future life feels abused and adrift in this paradigm of established art historical provenance, sculptural precedence and exhibitionary status. It stamps on everything I have the potential to become. However, L’Eau sat (and sits) supremely in opposition to every misogynist gesture embodied within the Butler canon. In my archival encounter in the Tate this knowledge played out in my head. Quite simply, it is an example of the Tate-as-archive serving as the site of an encounter where I make the judgement that Richier is ‘good’ and Butler is ‘bad’.

But, this is not a thought position about ‘good’ and ‘bad’ at a formal level. This is about how they operate as embodied categories for me as a student learning to know my art practice. Judgement is the moment at which I recognise my own positionality within the institution of UK sculpture pedagogy as an art student. This important moment of self-awareness consequently enabled me to acknowledge my position simultaneously both in that universe and my own sculptural making and pedagogic practice.

1 In 1970 Alistair Mc Alpine, British politician, businessman, author and art collector, gifted sixty sculptures from his collection to the Tate. The works were all by sculptors in what the Tate terms New Generation Sculpture. This collection included works by David Annesley, Michael Bolus, Phillip King, Tim Scott, William Tucker, William Turnbull and Isaac Witkin made in Britain in the 1960s. They were referred to as the Mc Alpine Group.

2 ‘Geometry of Fear’ was a term created by the critic Herbert Read in 1952 when reviewing the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in the same year. The works together were ‘characterized by tortured, battered or blasted looking human, or sometimes animal figures’ (Tate online learning resources).

Fig 8: Sheila Gaffney, A Philosophy of Generosity, 1982, charcoal, pigments, varnish, bronze, wooden table

Fig 9: Sheila Gaffney with A Philosophy of Generosity, 1982, charcoal, pigments, varnish, bronze, wooden table

The Manual for Making Sculpture

My method of learning, as a sculpture student, was to surrender to the sculpture object 'as a medium that alters the self' (Bollas: 1987) within the authorised archival history of British Sculpture (see Figure 8). This was my first subjective experience of the object (literally as sculpture but metaphorically as ideology) as a transformational object (see Figure 9). The encounter in the Tate-as-archive with the sculptures by Richier and Butler are, I believe, the consolidation of materialised psychic registrations, and this is an example of object relating, not just literally but psychically. The objects have cast their shadows without me being able to process, at that time, this relation though mental representations or language. In recalling my own act of study – that is, gazing upon forms which embody the UK sculpture pedagogy – I am undertaking what Bollas calls my own ‘emergent ego capacities’, where 'learning to handle and to differentiate between objects, and to remember objects that are not present, are transformative achievements as they result in ego change which alters the nature of the infant's internal world' (1987: 15). Bollas’s text The Shadow of the Object (1987) is now a deliberate strategy for thinking back and through the history of my own pedagogical inheritance. I use Bollas’ theory ‘The Transformational Object’ (1979) which argues that the infant's earliest experience of the mother is not as an object but as a process. How this maps through and within the culture of UK sculpture pedagogy is integral to understanding the concept of my thought position in sculpture.

When the text reads ‘we know that because of the considerable prematurity of human birth the infant depends on the mother for survival’ I believe a potential paraphrasing can be argued. The sculpture student enters the art school with a certain prematurity regarding the third dimension. We can hear this in Henry Moore’s canonical articulation ‘many more people are form-blind than colour blind’ (Chipp 1968: 594). Understanding this, one can read Bollas’s text as a manual for making sculpture. To demonstrate what I mean, I will paraphrase the opening paragraph of his chapter ‘The Transformational Object’ by inserting my own sculptural pedagogy as substitutions in italics. This sculptural reading of the term ‘object’ highlights the generation of a thought position within my own embodied knowledge of sculptural practice, derived from and informed by my encounter with existing works of sculpture and the derivation of my own antagonistic relation between them. I will now play a game of analogy to strategically put into place what Bollas is saying about the transformational object, but inserting UK sculpture pedagogy, so as to allow the specific context of this sculptural reading to come to the fore.

The student sculptor depends on the art school (that is the UK sculpture pedagogy) for survival… through it’s own particular idiom of mothering (i.e., studio practice pedagogy and in this case UK sculpture pedagogy). Lines 1-3

The UK Sculpture pedagogy’s way of holding the student, of responding to his [her] gestures, of selecting objects, and of perceiving the student’s internal needs, constitutes its contribution to UK sculpture pedagogy – British sculpture culture. In a private discourse that can only be developed by UK Sculpture pedagogy and student, the language of this relation is the idiom of gesture (making), gaze (visual analysis) and intersubjective utterance (the conversation initiated by the sculptor with student sculptor through which learning is practiced as a psychic model by the student in, through and with their practice). Lines 7-12 (Bollas 1987: 13)

The thinking of the making is the object relating. The making as thinking in this example employs the intersubjective utterances of ‘The Self as Object’ which is the topic of the third chapter of The Shadow of the Object.

I believe that through writing this thought position I am engaging in a necessary psychic writing out of sculpture making. Using the psychic framework of Bollas’s theory of lived experience and the frame of life writing I am demonstrating how a practitioner works with the psychic frame as an integral element of the sculptural imaginary.

Fig 10: Exhibition: Wuderkammer - the female gaze objectified, Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds, UK, 1994. Details: (Top Shelf LHS) Harry Phillips, Woman Undressing, Bronze, no date. (Lower Shelf LHS) Alfred Gilbert, Model for Chimneypiece, plaster, c. 1908. (Lower Shelf RHS) Peter Scheemakers, Model for Figure of Abundance, terracotta, c.1753. (Front) Sheila Gaffney, Pussy Pelment, wax, buttons, ribbon, bell, shoes, 1994. (Front LHS) Jocelyn Horner, Hands of Sir John Barbirolli, plaster, 1971-2. (Back LHS) Sheila Gaffney, Pleat, wax, 1994. (Top RHS) Hamo Thornycroft, Hand, plaster, no date. (Centre RHS) Sheila Gaffney, Girl, wax, buttons, ribbon, shoes, 1994.

Inside my head

When I am making sculpture it is my default position to think in, with and through the history of sculpture (see Figure 10). The work Reflections on The Good, The Bad and the Ugly is an example through which I may reveal this activity as a constitutive part of its exhibited presence. Such mental flux is not unusual. It has been depicted by Bruce Maclean in his The Generation Game of Sculpture, a cuddly toy, a ...no I've said that (2010) and in an email sent to me by the sculptor Paul de Monchaux, who writes:

We are formed by the past and are in constant communication with it, in our case via form, not words. When I was a child in the museums I felt I personally knew the artists who made the sculptures, however remote their place in time; I thought I could be like and with them, a member of a group with a common goal. I think it is this strong identification with work other than one’s own that is the fuel that propels us forward as artists. Whether literally, as with transcriptions, or imaginatively as in an awareness of a scale of standards. (De Monchaux: 2014)

Richier was understood to have ‘deliberately set up dialogues with masters of the past’ (Wilson 2005) in her practice. The purpose of writing this thought position out is to demonstrate the integral value of the generally overlooked, internalised and mental complexity of the maker. However, it is important to explore this with new tools in the complex field of contemporary knowledge. Bollas serves as one mechanism or channel through which a rationale for the chaotic mental interior of the sculptor may indeed contribute to the unique formations of sculptural thought.

Reflections on The Good, The Bad and the Ugly continues to model from a 1966 photographic register of my own lived experience to try and make sure what I am making is real, and not fantasy. In the essay The Self as Object (1987) Bollas tells us that:

People bear memories of being the mother’s and father’s object in ego structure, and in the course of a person’s object relations she re-presents various positions in the historical theatre of lived experiences. (1987: 41)

This concept is key to my thought position. I work haptically in, through, beyond and against the significant objects in my sculptural knowledge. Bollas affirms ‘It is an ordinary feature of our mental life to engage in sub-vocal conversations with oneself’ and ‘this constant objectification of the self for purposes of thinking is commonplace’ (1987: 41). In the literal act of making my ‘self’ as ‘object’ through sculpture, I also think, in and through the Tate encounter, which is a replay of my own internal theatre of lived experiences. In the same way that ‘much of psychoanalysis is about the nature of intrasubjective relations to the self as object’ (1987: 41) I would also argue that much of British sculpture has been about intrasubjective relations, inherited from the pedagogy, but between the self as object, the object as sculpture and sculpture to sculpture. In this work I have deliberately and strategically articulated my own position as sculptor and am literally handling myself as an internal object within the intrasubjective space of thinking through making. I am deliberately using the trope of what I call the ‘Watcher’ – my little girl muse of my six year old self. She is the self of object positions and is a pre shadow moment for me in UK sculpture pedagogy:

“Who is speaking?” – me as her, the modelled muse.

“What part of the self is speaking and what part of the self is being addressed?”

She (6 year old watcher), the student sculptor who is hurt by the ‘bad’ and full of hope from the ‘good’; and the I as now. All these parts of myself are speaking.

“What is the nature of this object relation?” Empowerment; to win; to exorcise the ‘bad’, to extrapolate the ‘good’ from the encounter, the intrasubjective utterances and to form language for my unthought known, to change the human factor in sculptural life modelling…and so on.

The sculptures of ‘good’ and ‘bad’, or Richier and Butler, are in play as holding persons and I believe this model accurately characterises the psychic activity which contributes to my making of sculpture. In his psychic model Bollas claims that the ‘person who possesses a capacity for intrasubjective relating is an object of her own self management’ (1987: 45). In my psychic sculptural model, the management of my self as object is a marker of owning my own practice. ‘The body memory conveys memories of our earliest experience. It is a form of knowledge which has yet to be thought and constitutes part of the unthought known' (Bollas, 1987: 46). My thought position here, the intrasubjective utterances which include my self as object, enables the modelling of thought as sculpture where the subjective becomes empowered within the self-regulated holding environment of my thought position as a part of studio practice. These recollections are not the chaotic mental ruminations of an older artist, but active autobiographical material for life writing as life modelling which signposts the diegetic triangulation of fiction, theory and autobiography. My archival encounter becomes instrumentally dynamic in the modelling of a true and ‘good’ register of what I will call ‘woman’ subjectivity. It is made to sit within the sculptural canon and confront the lingering, unchallenged, authorised ‘bad’ it contains.

Fig 11: Sheila Gaffney, claiming the good with Embodied Dreaming Class Forms, Leeds, UK: Leeds College of Art Gallery, 2015

Modelling Lines of Sculptural Thought

It is now 2015. I am presenting Reflections on The Good, The Bad and the Ugly (2015) in a public gallery. This work is part of my own return to modeling, a part of the ‘psychic prayer’ (Bollas, 1987: 17) that is studio practice, that is, the change of method a sculptor will employ within the search for the good sculpture. When I return to modelling, the theatrical categorical score of opposing sculptural ‘good’ and ‘bad’ resurrects its internal mental performance. With every touch of the wax surfaces I am forming in the modelling process to create my sculpture (which will be one of a series of bronze sculptures of girls), I am psychically returned to the formative object relation in the moment of this judgement. I need to win. I need to claim the ‘good’ in L’Eau and dispel the ‘bad’ in the Butler. It is time to legitimize my own symbolic capitol as a sculptor and change the history in figurative sculpture where men make feelings about women (see Figure 11). This is the thought position I now own as a sculptor. I am conscious of the ‘intersubjective utterances’ I practice as part of how I generate meaning in, through, and with, sculpture.

Sheila Gaffney is a sculptor and the Head of Fine Art at Leeds College of Art. Her current research explores through practice how and where the individual psychic frame of the sculptor in the broader field of British sculpture, which is not yet accounted for, embodies and plays out the concerns of classed subjectivity within a local UK history of sculptural practice. Recent publications include ‘Modelling Lines of Sculptural Thought: The Use of a Transcription Project to Interrogate, Intervene and Dialogue with a Sculpture Archive’ in Active Archives: Henry Moore Institute Essays on Sculpture 73; ‘Embodied Dreaming in the Archive’ in the Journal of Writing in Creative Practice Volume 7, Number 3; and the exhibition ‘Class Forms’ at Leeds College of Art Gallery in 2015. She studied sculpture at Camberwell School of Art & Crafts and the Slade School of Fine Art.

Website: www.sheilagaffney.com

References

Bollas, C. (1987), The Shadow of the Object: Psychoanalysis of the Unthought Known, London: Free Association Books.

BBC. 1974. Defying all but the most unconventional of conventions 22 January. [Online]. [Accessed 29 August 2015]. Available from http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/sculptors/12802.shtml.

Chipp, H. B. (1968), Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics, California: University of California Press

De Monchaux, P. 2014. Email to Sheila Gaffney, 14 April.

Elsen, A. E. (1974) Origins of Modern Sculpture: Pioneers and Premises. Oxford, Phaidon.

Jones, W. (2006), Grayson Perry: Portrait of the Artist as a Young Girl, London: Chatto & Windus.

Leinberger, C. (2004), Ennio Morricone’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, A Film Score Guide. Maryland: Scarecrow Press, Inc.

Mantel, H. (2003). Giving Up The Ghost. London: Harper Perennial.

Street-Porter, J. (2004), Baggage: My Childhood. London: Headline Book Publishing.

Tate. 2015. Geometry of Fear. [Online]. [Accessed 5 September 2015]. Available from: http://www.tate.org.uk/learn/online-resources/glossary/g/geometry-of-fear

Wilson, (S). 2005. Germaine Richier: disquieting matriarch. Sculpture Journal. Volume 14 (issue 1), 51 - 70.