Juliet MacDonald

Displaying the Head of Victory

(From left to right)

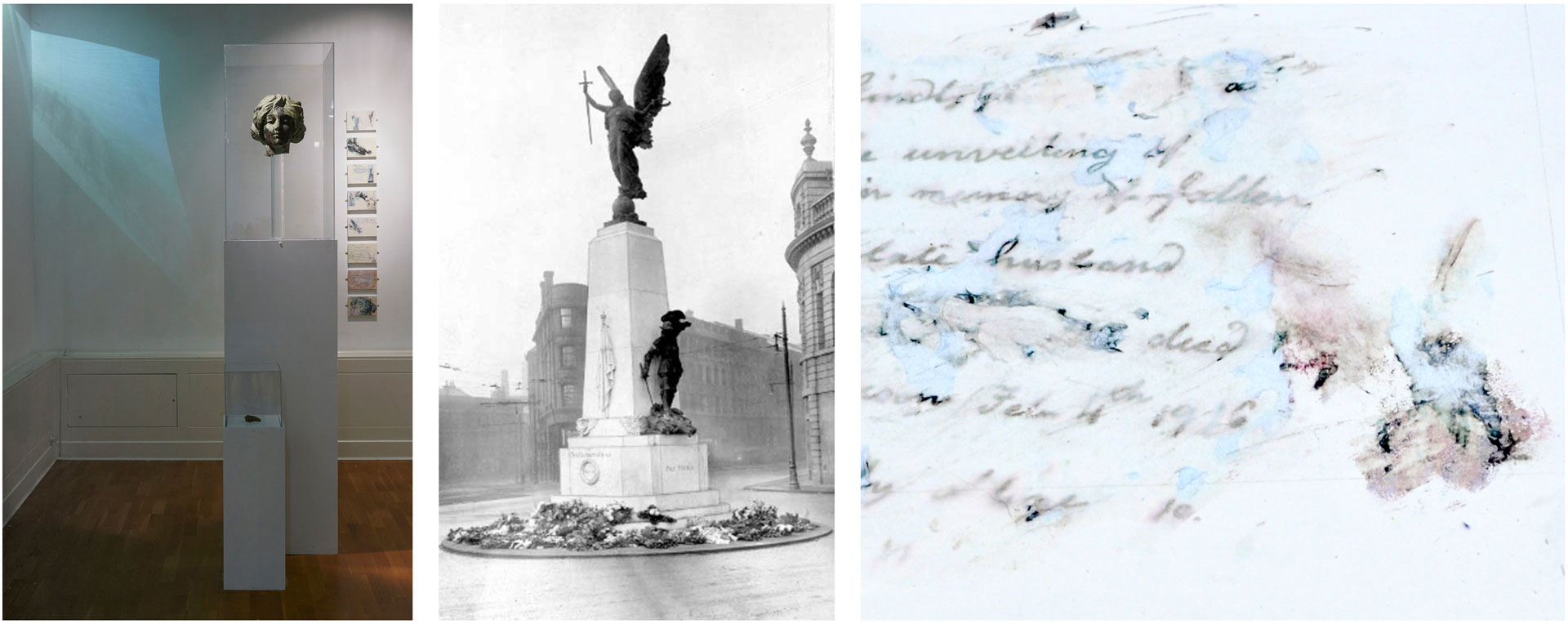

Fig 1: Head of Victory at Huddersfield Art Gallery [Installation view] Photograph © Jamie Collier, University of Huddersfield, 2015

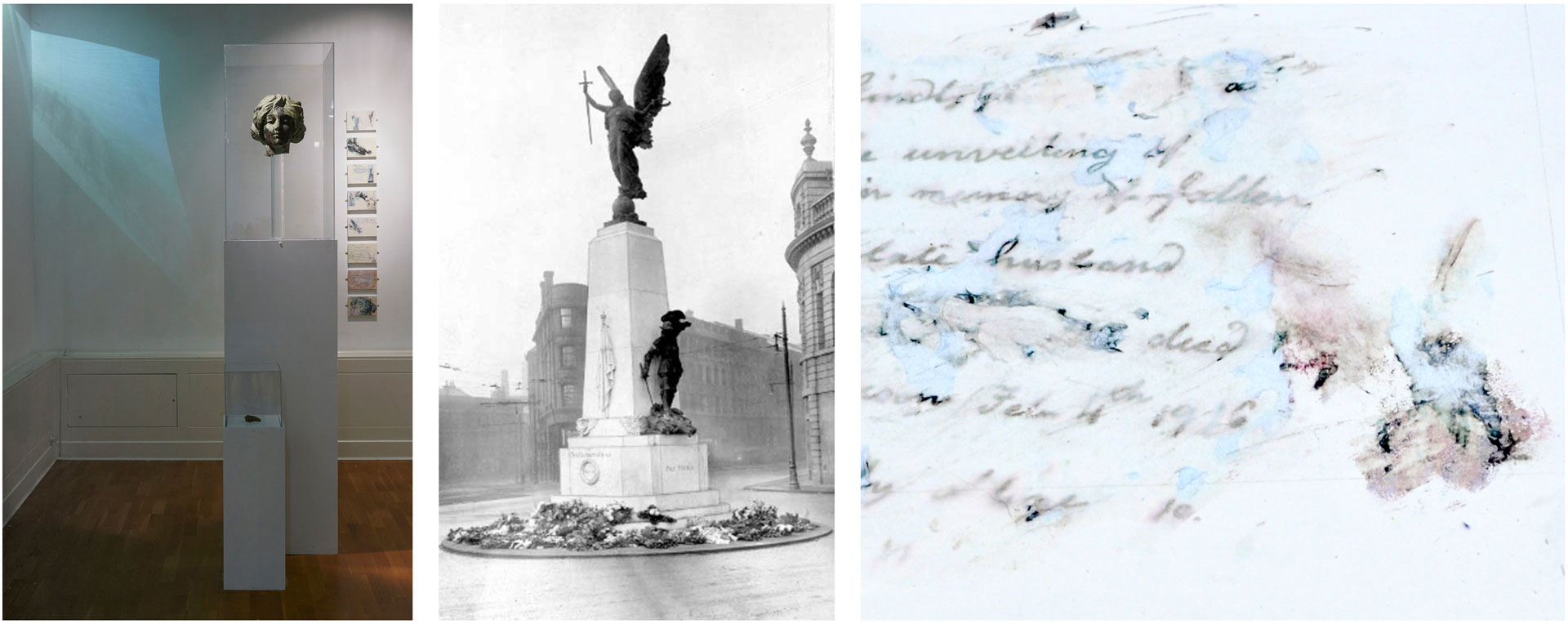

Fig 2: Henry Charles Fehr Leeds War Memorial (in City Square), 1922 Photograph ID 200296_64583987 © Leeds Library and Information Service www.leodis.net

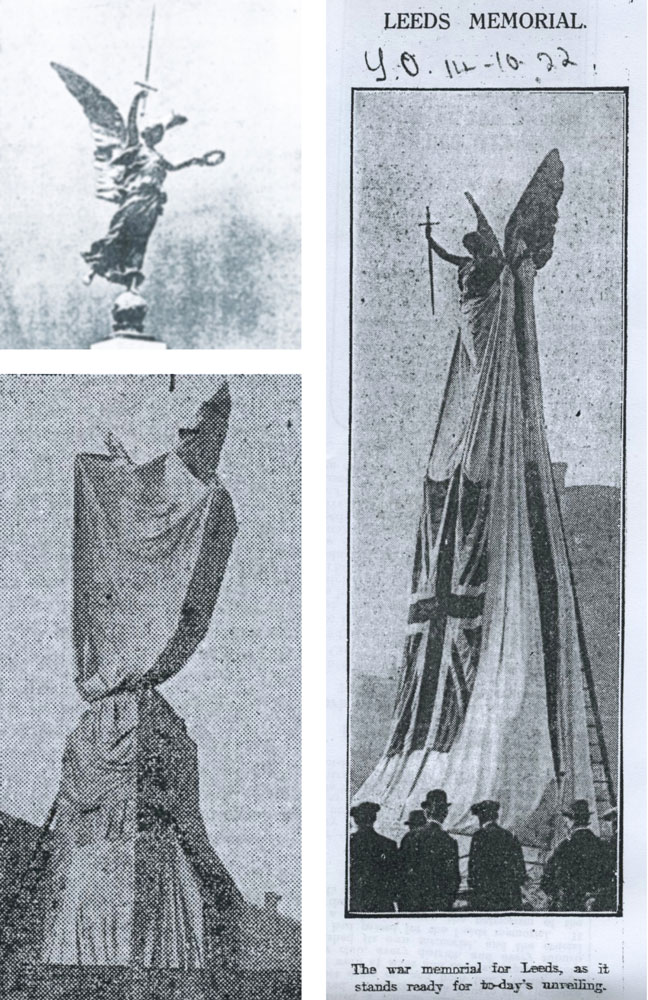

Fig 3: Juliet MacDonald Standing for the Fallen (detail), 2015 [Drawing/collage]

The Head of Victory is the only remaining section of the winged statue of Victory that once stood triumphantly at the top of the Leeds War Memorial. Created by the sculptor Henry Charles Fehr (1867-1940), the monument was installed in 1922 to commemorate those who died in the First World War. However in the decades that followed, the figure of Victory began to corrode and became increasingly unstable. It was removed from the memorial in the 1960s to avoid risk to the public. The head is now in the Leeds Art Gallery Collection, and has been very kindly loaned for the exhibition Thought Positions in Sculpture at Huddersfield Art Gallery. Here it is raised once more above viewers, flanked by two artworks that respond to the dual aspects of the memorial’s intended function, as a celebration of military victory and a monument for grieving families.

Historic Victory

The Leeds War Memorial was unveiled in October 1922 in front of a large crowd in City Square, Leeds. At the top stood the figure of Victory with wings stretching out and sword and laurel wreath held aloft. Two other statues stood at the base of the monument: Peace (a young woman holding a dove) and St. George (a knight slaying a dragon). The entire memorial was moved from City Square to The Headrow in 1937, where it remains today. The figures of Peace and St. George are still in position but Victory has been replaced by an Angel of Peace sculpted by local artist Ian Judd in 1991. The head is all that survives of the statue of Victory apart from one other very small fragment.

The history of the Leeds War Memorial has been well documented by Sarah Hanson (2010a). Drawing on painstaking research in local archives, Hanson reveals the commissioning of the monument to have been a very protracted process, much debated in the local press. A larger and grander memorial was proposed but insufficient funds were raised, so in 1921 Fehr’s cheaper solution was commissioned. Fehr was a well established artist, known for works such as The Rescue of Andromeda, 1893, which stands outside Tate Britain. His work features allegorical figures and classical motifs, the significance of which would have been more widely understood in the early twentieth century than they are today (Victory may have been inspired by the Greek goddess Nike). In the post-war period he was successful in attracting a number of commissions for public monuments, for example the war memorial in Colchester created to a very similar design as the one in Leeds.

Rather than viewing the monument solely as the achievement of a single sculptor, Hanson stresses the collective nature of the production process. Fehr’s proposal for the memorial was promoted by a former mayor of the city, Colonel T. Walter Harding, who had previously commissioned the Black Prince statue in City Square. The aims of a war memorial are outlined by Harding in a letter to the Yorkshire Post dated 28 January 1919: ‘Let us have something that shall be a lasting memorial of the sacrifices which were made by our citizens in a great and noble cause, and which shall inspire later generations with lofty ideals of citizenship, of patriotism, of freedom, and international justice’ (Harding, 1919). The planned memorial would not only commemorate those who died, it would act as a reminder of the values of the British Empire for which they lost their lives. This idealist and patriotic vision of the war aims and achievements of World War I has since been eroded by the persistent cultural impact of works of art that emerged from direct experience of the WWI battlefields, for example the bitter poems of Wilfred Owen or Paul Nash’s paintings of shattered landscapes.

(From left to right)

Fig 5: Henry Charles Fehr Peace (with dove, detail, Leeds War Memorial), 1922 [Bronze sculpture] Photograph © Juliet MacDonald

Fig 6: Henry Charles Fehr St. George (with dragon, detail, Leeds War Memorial), 1922 [Bronze sculpture] Photograph © Juliet MacDonald

Fig 7: Henry Charles Fehr Peace (Leeds War Memorial), 1922 [Bronze sculpture] Photograph © Juliet MacDonald

Fig 8: Juliet MacDonald Pax, 2015 [Digital image composite, based on Leeds War Memorial inscription]

In researching the figure of Victory, I have retraced Hanson’s route through the archives, viewing press cuttings in Leeds Local History Library and reading letters written by bereaved families to request tickets to the unveiling ceremony, which are stored in the West Yorkshire Archives. Hanson provides a timeline of the key events in the war memorial’s production and its ‘life’ as a public artwork (2010b: 28). This has been the inspiration for imagining a specific timeline of Victory against which twentieth century events might be marked. An initial set back in the memorial’s installation was the delay in arrival of the bronze statues from the foundry in Milan where they were being cast, causing a postponement to the planned date for the unveiling (Yorkshire Evening News, 1922). Correspondence in the Leeds Art Gallery Collection files reveals underlying structural problems in the figure of Victory itself. By 1940, cracks were noticed in the base on which it stood (a sphere representing the world, see Figure 11). Victory was removed for repair, but attempts to reinforce the globe by filling it with concrete only exacerbated the problem and although the statue was returned to the monument in 1946, by the 1960s cracks and instabilities in the base, body and wings were again causing alarm. The findings of a chemical analysis in 1965 revealed Victory to have been made of low grade or impure metal, rather than high-quality bronze. For health and safety reasons, the sculpture was again removed from the top of the memorial to a municipal yard at Sheepscar, near the city centre. From 1968 it stood at ground level in a rose bed at Cottingley Hall Cemetery, South Leeds, suffering vandalism, continuing to deteriorate and losing both its arms (Boorman, 1988). At some point after its removal from the cemetery in the late 1980s the head was detached from the body, which was reportedly ‘melted down’ (Roberts, 2007). The head was finally sent to the art gallery for safe keeping in 1998 having been found during renovations at Abbey House in West Leeds.

The idealism and instabilities of the figure and the concept of Victory are the main focus of my interest in this historical artwork. The chequered history of Fehr’s sculpture (described more than once in the gallery records as a ‘saga’), with its various repairs and relocations could be mapped against the post-WW1 history of the twentieth century. Britain made territorial gains after the First World War, for example in Palestine and Mesopotamia, and huge reparations were extracted from Germany after the Treaty of Versailles, but arguably these victories were overshadowed by subsequent events and conflicts. From 1939, Europe was again at war, and the post-WW2 period saw global politics dominated by the Cold War with Britain and the United States pitched against their former ally Russia. The long-term effects of WW1 campaigns in the Middle East, which resulted in a carve up of the region between British and French empires into spheres of influence and mandatory administrations, are still being played out in current conflicts in Syria and Iraq, and in the disputed lands of Israel and Palestine. Victory, it seems, does not equate to lasting peace.

(From left to right)

(From left to right)

Fig 9: Henry Charles Fehr Victory (Leeds War Memorial), 1922 Photograph ID 200296_64583987 © Leeds Library and Information Service www.leodis.net

Fig 10: Removal of the statue of Victory for repair, 1940 Photograph ID 20 200296_40290469 © Leeds Library and Information Service www.leodis.net

Fig 11: War Memorial, Headrow. Removal of bronze figure. Photograph 12343 © Leeds Art Gallery

Fig 12: The vandalized figure of Victory (at Cottingley Hall Crematorium, Leeds) Photograph © Derek Boorman, 1988 Reproduced with kind permission of Derek Boorman. This photograph appeared in Boorman's 1988 book At the Going Down of The Sun: British First World War Memorials, proceeds of which were donated to the Royal British Legion

Fig 13: Henry Charles Fehr Head of Victory, 1922 [Bronze sculpture], Leeds Art Gallery Photograph © Juliet MacDonald

Imagining Victory

Initially I had only seen the Head as a small digital image. I imagined it, or her, as a shell-like thing hanging above me, looking down from a distance with an imperious and detached expression. I imagined myself looking up into her hollow neck and carved out eyes.

As I found out more about her history I imagined her journeys, from the blazing heat of a foundry in Milan, crossing France in 1922, a landscape still scarred by battle, or travelling by boat across seas still harbouring submerged wrecks, to be winched up to her pedestal in Leeds City Square. And then later the indignities of further movements: re-sited on the Headrow, taken off for cleaning and repair, and when the serious cracks were starting to appear, dumped outside a suburban cemetery, exposed to vandalism. Rendered armless in both senses (lacking the sword and the limb to wield it), she was finally uprooted and sawn off at the neck, remaining only as a severed and empty head. Tracing her movements and trying to map them against points in history is one way to think through her significance as an object of past glory (and past grief) that has seen and suffered the vicissitudes of a turbulent century.

Thinking sculpturally, there are a number of striking features of this figure of Victory, for example its hollowness and its cracks. These are signs of vulnerability or lack of substance – a casing without any solid core. Cast from metal that was substandard or ‘impure’ (an alloy of whatever came to hand in post-war Europe, perhaps the best solution for the price or possibly an outright fraud), it/she becomes structurally unstable, swaying dangerously in the wind. This makeshift amalgam cannot retain its heroic form in the face of the elements. Over the course of time it begins to corrode and break apart.

Then there are the other missing bodies. Reading the letters from families requesting tickets to the to the unveiling, naming their lost sons, brothers or husbands, brought me back to a consideration of those for whom the memorial was made, and the very real, tangible, visceral bereavements still raw in 1922. Families of the dead needed to have a figure or a focal point for grieving and believing that it was all worth while – all done for the greater good, for justice, long-term peace and the civilizing British values of order, decency and fair play. An ideal is something to hold onto at a time of devastating loss. And wings are needed to dream of rising above pain.

(Top left) Fig 14: Henry Charles Fehr Maquette for Leeds War Memorial, Photograph © Yorkshire Post, January 1921

(Top left) Fig 14: Henry Charles Fehr Maquette for Leeds War Memorial, Photograph © Yorkshire Post, January 1921

(Left) Fig 15: Leeds War Memorial before unveiling Photograph © Yorkshire Evening Post, 7 October 1922

(Right) Fig 16: Leeds War Memorial before unveiling Photograph © Yorkshire Observer, 14 October 1922

Victory unveiled would rise triumphant, sword held aloft, enabling shattered families to come together in a public show of morning, letting go their private tears. But when the statue was revealed, the sculptor had turned the sword downward (Yorkshire Evening Post, 1922, October 16) so it was held forth like a cross, the blade gripped in her rigid, outstretched hand.

Now, with her body missing, Victory is just a decapitated head. Heads might be cut off in the course of human sacrifice, or heads might roll as a result of municipal blunders, but these are not the primary associations that strike me when looking at this trophy piece. In war decapitation is a sign of conquest, and here the victor has herself been vanquished. As a truncated head stuck on a post, she is rendered powerless. No longer a figurehead of civic or national pride she is merely a museum object, occasionally put on show but usually kept for safe keeping in the basement.

The frailties and fissures of the figure of Victory remind me of a holographic image, something that is ephemeral and insubstantial. I am also struck by her distinctive hairstyle. Both these strands of thought bring me to YouTube and Princess Leia’s flickering holographic message to Obi-Wan Kenobi, a plea for help transmitted from a distant galaxy (Lucas: 1977). Why Star Wars? Why now? As unmanned drones patrol far off skies and unknown enemies with the power to decapitate transmit messages of warning to countless screens, what fearful clash of Empires might the future bring? Is it possible to imagine?

(From left to right)

Fig 17: Henry Charles Fehr Head of Victory, 1922 [Bronze sculpture] Leeds Art Gallery Photograph © Juliet MacDonald

Fig 18: Head of Victory at Huddersfield Art Gallery [Installation view] Photograph © Alina Pankova, Photography BA(Hons), University of Huddersfield, 2015

Fig 19: The British Army in the Sinai and Palestime Campaign, 1915-1918 Photograph © IWM (Q 12702)

Thinking through Victory

In my response to the sculpture Head of Victory, my first thoughts concerned the demarcation of space.

One of the First World War victories for Britain was at the expense of the Ottoman Empire. In 1917-18, British-led forces under the command of General Allenby successfully advanced North from Egypt through Palestine and into Syria, reaching Aleppo by October 1918. In Mesopotamia, another British Empire expeditionary force captured Baghdad in March 1917, continuing North to apply further pressure on the on the Ottoman held territory. Although the stated aim was to liberate Arab populations from Ottoman control, the interests of the British Empire included oil pipelines in Persia and vital trade routes through the Suez Canal. The secret Sykes-Picot agreement had already been signed between Britain and France, with the acceptance of Russia, to establish spheres of influence within the region in the event of an allied victory. Within four years of the end of the war mandates were established so that by 1922 (when Fehr’s statue was unveiled) Syria and Lebanon were under the administrative control of France, while Britain controlled Palestine and Iraq. Lines drawn on the map by French and British diplomats pre-figured the division of land and distribution of resources in the region.

Initially I thought of positioning the head so that it would literally cast a shadow over a map to indicate that a First World War victory had left its traces on a part of the world that is still in conflict. In 1922, the face of Victory would have looked down with a distant, imperial gaze as though surveying her conquests: supreme and unassailable. How had the power of empire, which this statue previously symbolised, unravelled over the course of a century? When I saw the sculpture in the secure basement of Leeds Art Gallery in 2015, it was supported on a long Perspex tube. The face was worn and discoloured. As a relic of past glory it might have potency – that of a totem perhaps – but as a decapitated head on a pole, it could be seen instead as the trophy of an opposing power. Displaying it at a height was a means to leave both interpretations open. The plinth is monumental but the viewer is able to look up into the neck and see the hollowness of both the ideal form and material substance of this Victory.

In front of it/her is a small fragment of her own shattered body which she peers down at. Behind her is the spectre of former conquest: early film footage of British troops in the Sinai Peninsula and extracts from a post-war propaganda film celebrating Allenby’s campaign in Palestine and Syria (Imperial War Museum, 1917 and 1919). It became apparent to me in looking at this footage that the step-by-step march of columns of heavily loaded camels and horses is itself a demarcation of territory. Much slower than it would be today and not immediately recognisable as a scene of warfare, the steady advance of harnessed animals, walking men and slowly moving vehicles through such a difficult terrain constitutes a declaration of power. In the installation, which I have entitled ‘Victory in the Desert’, 2015, the projected image is deflected from the ceiling by a sheet of acrylic and a bundle of net curtain (a veil for my purposes). It spills down one wall and across another. This displacement detaches the digital video from the seeming veracity of black and white archive footage. Mounted troops and vehicles become instead the space invaders of a distant and foreign Empire, leaking out of the historical records in a pale green-blue fan of light.

Victory’s downcast eyes could also be an expression of grief. It is a tribute to Fehr’s skill that the face he modelled could suggest both distain and sorrow, personifying both aspects of a grieving but triumphant nation – the goddess of victory in mourning for those who died in her name.

The effects of erosion and deliberate vandalism intensify the association with violent loss of life. Derek Boorman’s 1988 photograph shows Victory standing in a rose bed (Figure 24) with amputated arms and flightless wings, and folds of fabric carved out like layers of lacerated flesh.

Now only the head remains. The crude cut marks to the base of the neck show that the rest has been scrapped, but in the archives are letters from bereaved families asking for tickets to the unveiling ceremony. They are a tangible reminder that this was once a significant object for thousands of people to gather around, publicly sharing their sorrow for lost sons, brothers, husbands and fathers.

‘As the singing gathered in power one could not resist a swift retrospect of those four black years – years in which wife, mother and father drank deeply of the cup of agony. In a short time the whole of that mighty campaign, with its moments of pain and of hope, were lived over again. “Cover my defenceless head, With the shadow of Thy wing.” Everyone could not sing those words. There was a lump, which even the hardest must have fought with. Heads hung down to hide the falling tears’ (Yorkshire Evening Post, 1922, October 14).

The letters from families were the basis for eight small drawings or collages entitled ‘Standing for the Fallen’, 2015. The technique I used to make them was experimental. Using a basic household inkjet printer I made reversed copies of photographs of the memorial, and press cuttings and letters from the archives. After coating them in wet PVA, I stuck the prints face down onto drawing paper. Before they dried, I doused the back in turpentine, which softened the cheap inkjet paper so that it could be peeled away, leaving just the toner ink itself and a few fibres sticking to the surface. The process was unpredictable; the whole thing tore at times. No matter what colour the print, the residue remaining after these solutions had been applied was either a sickly pink or a green, similar to the colour of oxidised bronze. The process seemed strangely violent because the back of the inkjet paper was effectively ripped from the front. As a three-dimensional object the piece of paper had been severed along its thinnest dimension, its least tangible axis.

With these artworks I have tried to consider the eroded Head of Victory from two different angles, as figure of glory and monument to loss.

(From left to right)

(From left to right)

Fig 20 - 23: Juliet MacDonald Standing for the Fallen (work in progress) [drawing/collage]

Fig 24: The vandalized figure of Victory (at Cottingley Hall Crematorium, Leeds) Photograph (detail) © Derek Boorman, 1988

References

Boorman, D. (1988). At the Going Down of the Sun: British First World War Memorials. York: Ebor Press.

Hanson, S. (2010a). Anatomy of a Monument. In: Henry Moore Institute Online Papers and Proceedings. Retrieved from: http://www.henry-moore.org/hmi/online-papers/papers/sarah-hanson

Hanson, S. (2010b). Further research from Anatomy of a Monument. In: Henry Moore Institute Online Papers and Proceedings. Retrieved from: http://www.henry-moore.org/hmi/online-papers/papers/sarah-hanson

Harding, T. W. (1919, February 3). Leeds War Memorial [letter dated 28 January]. Yorkshire Post.

Imperial War Museum (1917). Siwa Expedition [film]. (IWM 5).

Imperial War Museum (1919). Allenby’s Campaign [film]. (IWM 1095).

Lucas, G. (1977). Star Wars. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pUaxXsqGeFI

Roberts, D. (2007). Sculpture: Henry Charles Fehr Head of Victory (1922). Retrieved from: http://www.leedsartgallery.co.uk/gallery/listings/l0061.php

Yorkshire Evening News (1922, September 30). Leeds War Memorial.

Yorkshire Evening Post (1922, October 14). Lord Lascelles Unveils Leeds Cenotaph. A Worthy Memorial.

Yorkshire Evening Post (1922, October 16). The Pendant Sword.